THE LAST WORD ON CHAIN LUBRICATION

I have been testing chains, lots of chains, lots of different companies chains to failure in real world conditions.

Mostly, I have been testing how 11-speed chains work on 10-speed drive trains. Also, I started looking closely at lubes and the role they play in overall chain functionality.

I have read numerous lubrication testing articles, what works, what doesn’t and why. This includes the infamous Velo News/Friction-Facts testing articles during 2013 where they concluded that a wax-based PTFE lube is best.

Since PTFE will not stick to anything and nothing will stick to PTFE, Friction-Facts solves this by suspending the PTFE inside their wax (and Finish Line suspends PTFE inside their Dry Teflon® lube).

In theory, Friction-Facts wax with PTFE makes for a great chain friction inhibitor … as long as the wax stays between the plates, pins and rollers.

In real world conditions, this does not work as well as in the laboratory. In real world cycling, you are shifting the rear derailleur up and down the gears dozens and dozens of times during a ride.

From what I can tell of the Velo News testing, the machine they used kept the chain in-line between the front and rear sprockets. Only a load to simulate 250 watts was applied to the rear cog. Another factor not mentioned was torque load. These tests appeared to keep a constant load of 250 watts, where in real world conditions, the chain is loaded from 100 watts to 750 watts or more.

If the chain is not inline during peak wattage, then the wax lube is sheared out between the plates, pins and rollers, never to return. This is the issue with wax-based lubes.

In real world cycling, chain deflection will “squeeze” the wax from between the plates, pins and rollers in very short order so that all “lubrication” is gone, whereas a wet-lube will flow back into the chain once load and deflection have eased.

Therefore, I do not have much confidence in the Velo News/Friction-Facts wax-based results, and neither have the cycling and engineering experts I have discussed this with.

So what Lube Works Best?

I have consistently been getting between 3,200 to 3,500 miles on each 11-speed chain. So why do some chains last

3,200 miles and others last 3,500 miles?

3,200 miles and others last 3,500 miles?

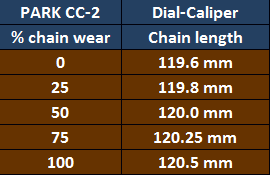

First, each chain is measured every 200 miles for wear. I used the Park CC-2 pin measurements to translate to a dial caliper. The following measurements were verified by Park Tool as being within tolerance.

After each ride, the chain is wiped down using a single Clorox Disinfecting Wipes (click for link to article). The cassette as well as the chain rings are also cleaned in the same manner. Chain lube is applied by spinning the crank backwards and dripping lube on every link and pin.

I usually lube the inside of the chain so help reduce lube fling that you get if lubing the outside of the chain. Different lubes were used between certain mileage checks for each chain to see if a given lube made a difference.

ProLink was used from 0 – 1000 miles for every chain. Finish Line Dry Lube with PTFE from 1000 – 2000 miles, Shell Rotella T6 from 2000 – 3000+ miles.

No difference in the amount of chain wear was seen between any of these intervals on any of the chains which shows that a full synthetic engine oil works just as well as a small 4 ounce $11 bottle of special purpose bicycle chain oil.

- Lubrication – during my testing, I have found it better to use a wet-lube than a dry lube. I know cyclists prefer dry-lubes since they are cleaner and require less maintenance. Wet lubes work better but the drawback is that the drive train takes longer to clean. More importantly, wet lubes flow better than dry lubes. Meaning that as chain deflection forces lube from between the parts of the chain, as deflection decreases, a wet lube will flow back into these critical wear areas.

- Lubing – It’s better to over-lube a chain than to under-lube a chain. I’m not talking about the top and bottom of a chain, I’m talking about the amount of lube. There is one LBS owner that swears by the old wives’ tale to place a drop of lube every 3rd link. The theory is that the front chain rings will pick up the lube and distribute to the remaining links. His, and his customers chains last 1,000 miles. I just think he’s trying to sell more chains to his customers.

- 10-speed vs 11-speed chains – What I have found out is that 11-speed chains are more accurately built than 10-speed chains. Higher precision is required and tolerances are a lot tighter on 11-speed chains, so, they are setup with absolute minimal measurements. In the past, I have measured brand new 10-speed chains and the Park CC-2 and would indicate that a certain brand new chain was already close to 50% worn while other 10-speed chains indicated 35% worn. These tolerances were all over the map. With the advent of 11-speed chains, I am seeing initial measurements of 119.30 which indicates about -30% worn. Yes, negative 30% worn! In fact, I couldn’t even get the pins of the CC-2 between the pins of the chain. Of the chains I have tested, the average new 11-speed chain measures 119.50 mm.

CONCLUSION

- Use the newer 11-speed chains on your 10-speed drive train.

- Clean the chain after each ride.

- Over-lubing is required to get higher mileage out of a chain.

- The best chain lube is a wet-lube.

- Use a lube such as Synthetic Shell Rotella or Mobil 1 instead of a high priced specific bicycle chain lube.

WHY?- Because, it really didn’t matter what wet-lube was used, total mileage and performance was the same.

- A high quality synthetic engine oil costs $1.50-$1.77 for 4 ounces, vs about $11.00 for a 4 ounce bottle of bicycle chain oil. Synthetic oil has an added advantage of its molecules being the same size – i.e., less friction than mineral based oil.

WHAT MATTERS MOST IS THE INITIAL CHAIN MEASUREMENT

The Park CC-2 measures 119.6 mm at 0% wear. The new 11-speed chains measure less than that – consistently. Several new 10-speed chains showed close to 50% worn out of the box. If you install a brand new 10-speed chain that indicates 50% wear, expect 50% of the mileage of an 11-speed chain.

CASSETTE NOTE:

Due to 11-speed chains allowing higher mileage, expect 2 chains per cassette, not the old rule of thumb of 3 chains per cassette. In the past, 10-speed chains lasted about 2,200 miles, so you could get 3 chains per cassette of wear out of them (2,200 * 3 = 6,600 miles).

11-speed chains are averaging about 3,300 miles, so you can only get 2 chains per cassette out of them (3,300 * 2 = 6,600 miles).

I have always enjoyed bicycling and, through a series of coincidences, became a Bicycle Industry Consultant and Product Tester. I test prototype products for companies and have published only off the shelf production products on biketestreviews.com.